Reflections on the shortest US recession in history

It’s official. As announced on 19 July, the United States National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) determined that last year’s US recession* ended in April – just two months after it began!

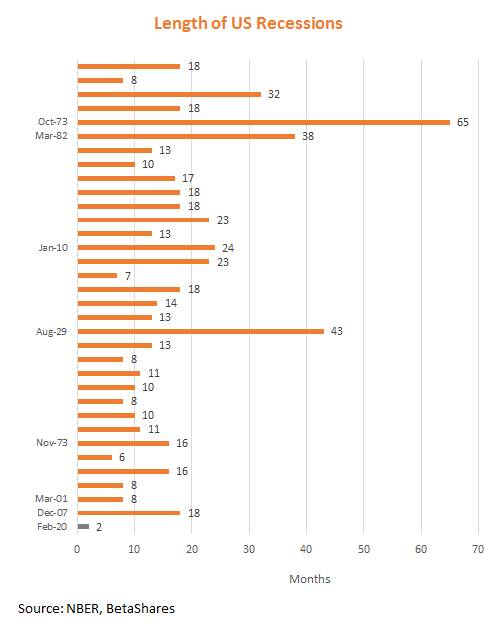

As seen in the chart below, that means last year’s recession was officially the shortest in US history. Since records began in the 1850s, the average length of a US recession has been 17 months, though the average since World War 2 has been 10 months.

The 2001 recession – following the dot-com bust and September 11 terrorist attack – lasted eight months, while the recession during the 2008 global financial crisis (GFC) lasted a relatively lengthy 18 months.

With the growth in the (more stable) services sector relative to manufacturing and agriculture, US recessions have tended to get shorter over time – though as evident during the GFC, recessions can still last a considerable time, particularly if associated with a financial market collapse, delayed policy stimulus, and damage to business and household balance sheets.

With hindsight, last year’s “recession” was more akin to a natural disaster event, in which widespread initial “lockdowns” in major cities such as Los Angeles and New York caused an immediate collapse in employment and economic activity. What was remarkable last year was not the stock market recovery per se, but that America’s economy became increasingly resilient even as it experienced multiple waves of COVID.

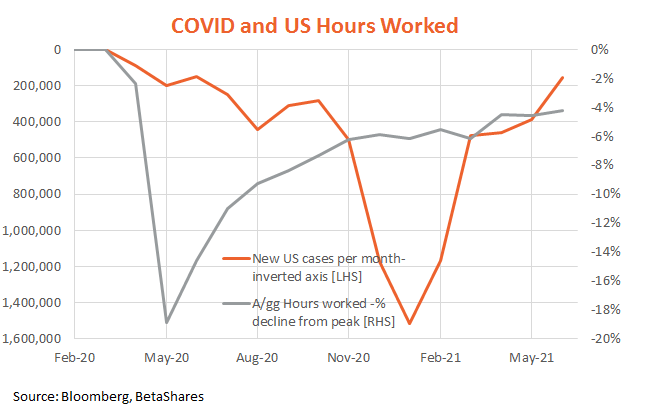

As seen in the chart below, US aggregate weekly hours worked collapsed by 18% in the two months to May. But thereafter they began to gradually recover even as the US endured two further significant COVID waves – each worse in terms of total cases reported than the previous one.

This likely reflects the fact that other US cities resisted the stringent lockdowns first evident in New York and California (for good or bad, as this likely also resulted in more COVID cases!) and also reflected significant fiscal and monetary stimulus that led to a strong upturn in home building and consumer spending.

Although the NBER usually announce the beginning and end of US recessions with a considerable lag (last year’s recession was not announced until June 8 2020) these dates do offer an important historical record against which to assess the performance of financial markets and the economy.

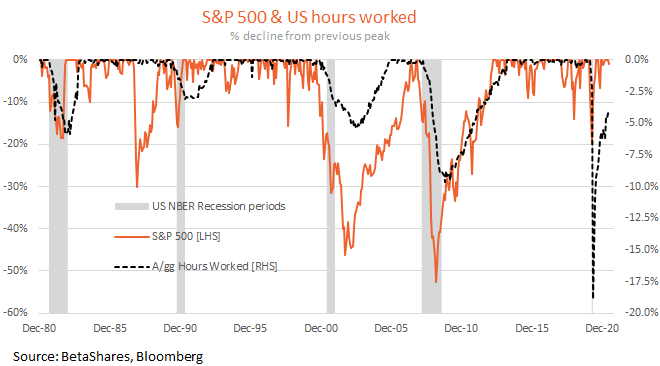

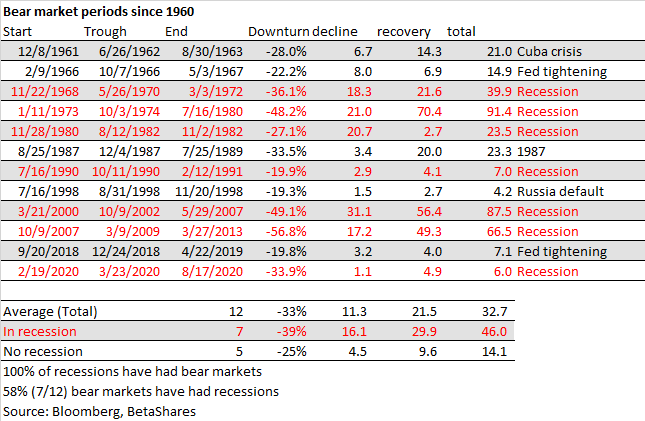

In terms of financial markets, it should be no surprise that US recessions are usually associated with equity bear markets (a greater than 20% price decline in stocks). And typically, US bear markets bottom out a few months before recessions end (the 2001 bear market being a rare exception).

In this regard, the US equity market last year performed exactly as might have been expected given the recession only lasted two months! The shortest recession in history was also associated with the shortest recessionary bear market in history of just over one month. Since the early 1960s at least, the average length of a bear market associated with recession has been 16 months – the previous shortest recessionary bear market was 2.9 months during the 1990 recession.

Of course, while it’s tempting to say “the market got it right”, in reality the market rebound began in anticipation of a bottoming of the economy that was gradually validated by the evidence. Had the economy not bottomed that quickly, it’s unlikely the equity market would have either.

*Note a US recession is a qualitative assessment by a committee based on a review of a range of indicators. To be classed as a recession, a downturn must involve “a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months”. Although very short, the NBER defined last year’s downturn as a recession due to its depth and breadth. Note there is no such Committee in Australia, or most other countries for that matter, where a recession instead tends to be “technically defined” as two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth. This is naturally an imperfect measure, as a long period of weak but positive growth could also entail a substantial rise in unemployment – as could negative quarterly GDP but not over successive quarters.

4 topics