The risks of going cashless

Beggars in China with QR codes hanging around their necks and others pleading with matrix-barcoded tins caused a stir when they appeared on Chinese city streets in the past year or two. Fellow Chinese shouldn’t have been surprised. These beggars are only keeping up with one of the most-rapid trends of Chinese society – going cashless.

Mobile payments in China surpassed 39 trillion yuan (US$5.5 trillion) in 2016, up 215% from 2015 and more than 50 times US mobile transactions. Online shopping, lending, betting and investing are booming in China and even physical retailers are catering for the virtual wallets offered by Alibaba’s Alipay and Tencent’s WeChatWallet.

China is not alone in moving on from paper notes, coins and cheques – but the Chinese skipped the plastic card stage. It’s a worldwide drift.

Global non-cash transactions reached US$23.1 trillion in 2016 to overtake cash payments for the first time.

In Australia, where non-cash payments comprise 52% of total retail outlays, electronic payments are set to climb in 2018 when Australia joins a handful of countries such as Mexico and Sweden that have ‘real time’ payments systems that connect customer bank accounts.

People the world over are turning to payments technologies because they offer many advantages over cash. People find going cashless is a safer, more convenient and quicker way to pay bills. They can buy from strangers over the internet. With credit cards, people can earn rewards and borrow easily from respectable companies rather than ‘loan sharks’ or pawnshops. If fraud occurs, the payment companies bear the loss. Merchants like that it brings forward purchases, an acceleration of retail spending that helped fuel global economic growth over the past three decades. Charities like that many people don’t even notice they are regularly donating once they have given their credit-card details. Governments promote the trend as many cash transactions avoid tax, are linked to corruption, or are tied to crime – and because politicians want to look innovative. For economists, a cashless society boosts the effectiveness of negative interest rates as a weapon against deflation because no cash would escape the cost of negative interest on digital accounts.

But a cashless society, as popular and advantageous as it is, comes with challenges.

The easy access to consumer credit comes with punishing interest rates that tend to fall on low-income earners. Electronic transfers have social and political ramifications that include privacy issues. Card fraud is a bigger risk on the insecure internet. Menacingly, the cashless society has spawned stateless virtual currencies and other unregulated web-based finance that are not backed by normal safeguards. The shift to a cashless society could be rockier than expected.

Cash is a long way from disappearing, it must be said. Society probably doesn’t want to eradicate cash anyway; otherwise, kids buying lollies at the corner store would need plastic cards. The trend faces ideological resistance because some people view cash as a ‘public utility’ that should not be privatised for profit. Security concerns might limit the shift and criminals will defy it. Many advanced countries are slow adopters. The US, for instance, is stuck with notes, cheques and signed-card use because the many types of point-of-sale payment terminals confuse people. Asia ex-China favours cash too, even wired Singapore. Going cashless too abruptly can backfire as India’s shock ‘demonetisation’ of 2016 showed. But technological advancements and the advantages of e-payments over cash make a more cashless society inevitable. No major financial change is frictionless. Hopefully the ripples and risks associated with the shift to paying via cards, mobiles, apps, the internet and cryptocurrencies can be kept in check. There is no reason why they can’t be.

A carded world

In 1949, a US businessman couldn’t pay his restaurant bill because he forgot his wallet. His wife had her purse and paid but Frank McNamara’s embarrassment gave him an idea. A year later, McNamara invented the first modern credit card when he introduced the Diners Club Card, even if it was a (cardboard) charge card in that the bill had to be paid at month end. By 1953, the Diners Club Card had gained acceptance outside the US.

Other companies, such as American Express, Mastercard and Visa, as they are named today, soon saw the opportunity. The card companies’ selling point for merchants, who face a charge on turnover, was that people would buy items they wouldn’t have otherwise (even as merchants recouped their fees by boosting prices).

One proof that cashless payments promote more spending is that behavioural psychologists are advising spendthrift people to switch back to cash if they want to better control their urge to spend. Psychologists say that cards boost the propensity to spend on non-essentials by up to 50% while the payments data that companies collect hones the ability of marketers to target consumers.

While credit-card debt is a small component of household debt – the majority is mortgage-based and some is car and student debt – credit-card debt comes with harsh interest rates for those who borrow this way and is the part of household debt most exposed to an economic downturn, especially as the debt is generally short-term lending to low-income households.

Australia’s 7.8 million credit-card users, for instance, are paying an average interest rate of 16.6% on $32.8 billion of the $50 billion amassed on credit cards, according to ASIC’s ‘credit card debt clock’, when the Reserve Bank’s cash rate is only 1.5%.

Another concern with a society going cashless is cyberfraud, which at some elevated level would unwind the economics of credit cards for their issuers. While no major payments networks or banks have succumbed to crippling incursion, a credit-reporting agency, which houses even more sensitive data, has. In 2017, Equifax of the US admitted a cyberattack had compromised the records of 143 million US consumers, which could help accelerate the rise of online credit-card fraud. In Australia, credit-card fraud in 2016 reached $534 million, or 74.7 cents on every $1,000 spent on cards, up from 51.5 cents in 2011. In the US, fraud has reached US$1.18 per US$1,000 spent on cards while in the UK it’s 83 pence every 1,000 pounds.

Going cashless comes with social and political consequences that dim the trend’s appeal for many. Disadvantages include that it erodes privacy as all transactions are traceable. Another concern is that the data can be sold to advertisers – even China’s barcoded beggars act for marketers. Another social cost is that poorer and older people who are locked out of the ever-more-digital banking system fall further behind.

On the political side, some people worry that reducing cash in circulation is an “ugly power grab by Big Government”. The use of ‘cashless welfare’ cards to limit spending on alcohol and gambling shows such views have a point – Bill Shorten says people are being treated harshly “to get a headline in the big cities” – though it’s no different from how ‘food stamps’ are used in other countries. A more valid concern is that authoritarian regimes can know who is spending what. China’s government, which has visible and invisible reins on Alibaba and Tencent within China, is accumulating that power.

A cashless society gives the US government more diplomatic (political) power it can flex because the biggest card companies are from the US. In 2010, to much controversy and revenge hacking, Mastercard, PayPal, Visa, Western Union and others acquiesced to US government pressure and blocked donations to WikiLeaks for revealing secret US diplomatic cables even though the whistleblowing site that is dependent on such assistance had breached no laws. The payments companies are addressing this concern by processing certain countries’ domestic transactions in data centres located within their sovereign territories. Countries such as China and Russia have insisted this be done to minimise US influence over their financial systems.

The blockchain solution

The greatest risk associated with the rise of cashless transactions is surely the advent of coded software known as cryptocurrency.

While cryptocurrencies are money in an economic sense because they are a means of exchange, they aren’t in a legal sense. That’s what makes them troublesome in theory and, since they are in a speculative bubble, dangerous in practice.

Modern state-issued fiat currencies (those not backed by a physical asset such as gold) are part of a government-controlled trust-based financial system. Governments, via their central banks, undertake many tasks to preserve the value of money. Policymakers guard against counterfeiting, ensure enough cash is in circulation, keep inflation low, accept payments in the currency, ban the use of other currencies and operate clearing houses. Above all, central banks stand behind government debt and secure the banking system by acting as the ‘lender of last resort’ to banks, ensuring that individuals can access their funds at bank accounts.

A key feature of the state-backed currency systems is that when a central bank issues fiat money it incurs a liability that ultimately harks to the creditworthiness of the country. Bitcoin is a risky development because it was inspired by anarchists who wanted “a purely peer-to-peer version of electronic cash”. Thus, with Bitcoin, no central authority issues this cryptocurrency. Nor does any central body incur a liability. This makes cryptocurrencies ‘assets’ like commodities, not fiat money. But cryptocurrencies are maths-based digital assets that have no intrinsic value. Most other assets, in contrast, from property to gold to paintings, have alternative uses and scarcity that gives them some inherent worth.

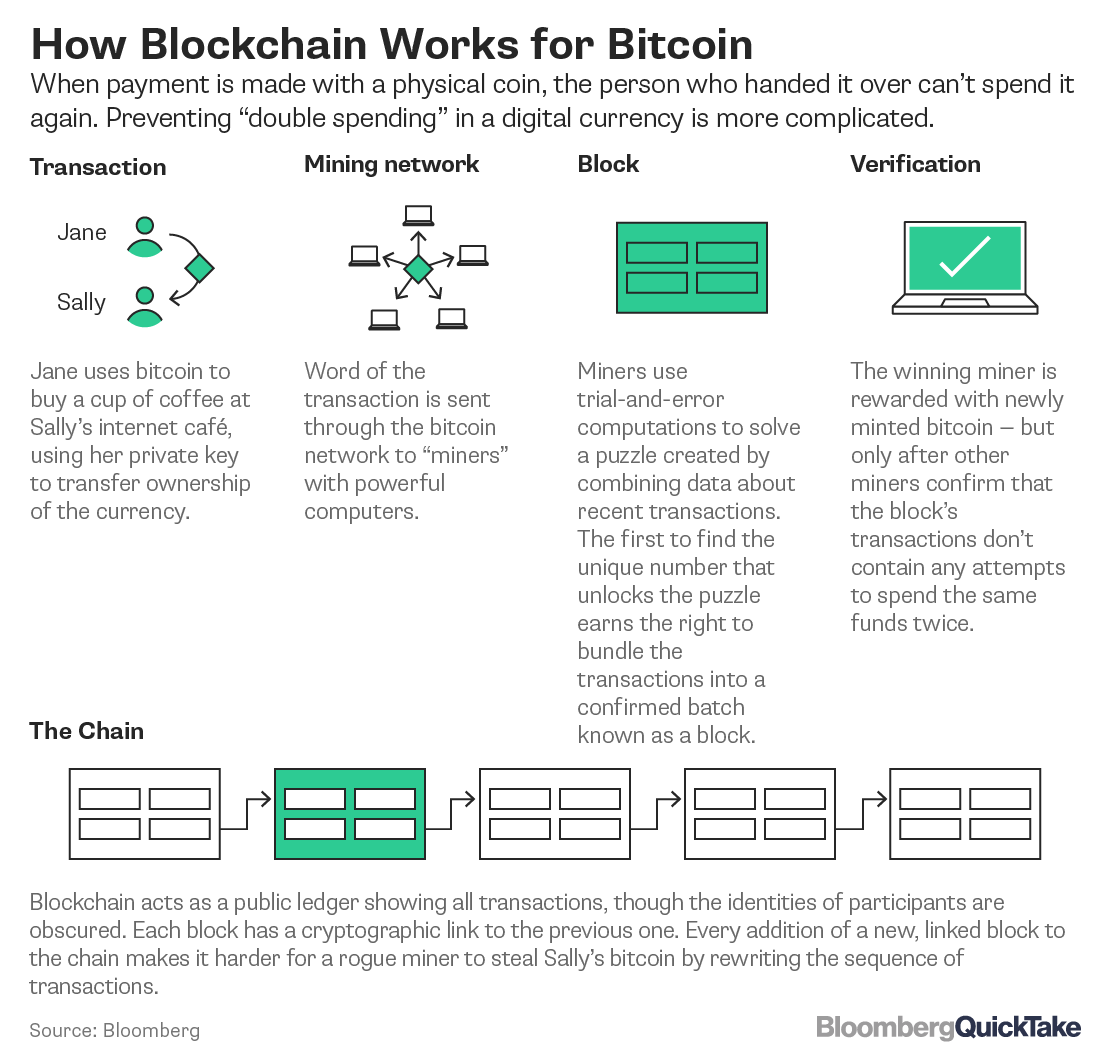

Online games such as Minecraft invented digital money to make their games competitive. The obstacle the online world needed to surmount to move from play money to digital payments was to prevent counterfeiting. The anonymous anarchist(s) behind Bitcoin solved this problem by inventing the counterfeit-proof ‘blockchain’, the name given to the digital ledger that records every transaction to ensure each Bitcoin spent is unique. (The blockchain now has legitimate uses beyond this purpose, such as trade settlement and asset registers.) Bitcoin’s blockchain is run by ‘miners’ who validate transactions. A decentralised mechanism drips out bitcoin as a reward to the first miner to validate the latest batch of transactions in chronological order. The system is essentially based on mathematical proof, not trust in a sovereign, and is managed by user consensus.

Useful but risky

Historically, in some countries, private banks issued money so there is precedent for private-sector-backed currencies gaining mainstream use. Bitcoin gained acceptance because it comes with advantages – as long as it can be readily exchanged for state-backed currencies anyway. It reduces payment costs and time, especially across borders. People and businesses in countries such as Venezuela and Zimbabwe, where faith in money is shattered, have another option besides sovereign currencies. Criminals like Bitcoin because, while the transactions are publicly recorded, users can stay anonymous by operating behind untraceable virtual addresses. There is nothing to stop governments issuing cryptocurrencies, which would eradicate the flaws tied to their statelessness.

Central banks issuing cryptocurrency and then recording every transaction for perpetuity on a central ledger, however, would give authorities permanent surveillance over every transaction, an ironic outcome for an anarchistic invention.

Bitcoin’s success as a means of payments has spurred the emergence of more than 850 other digital-currency platforms even if more than 20% of them appear to have failed, many more seem headed that way and each cryptocurrency platform has different ways of issuing additional coins. More crucially, cryptocurrencies have become speculative investments. Those speculating are assuming Bitcoin will stay a means of exchange and will be easily converted into state-backed currencies. In a sense, Bitcoins are valuable because people think they are valuable, the diciest basis for any price surge.

Users of and especially investors in cryptocurrency should be wary because the cryptocurrency world of today is opaque, borderless and operating beyond the control of national governments. The speculation surrounding virtual currencies limits their reliability as a store of value. No consumer protections exist. No mechanism is in place to resolve disputes that might arise if a digital currency loses its value, fraud occurs, hacking triggers losses, someone wants to retract a payment or digital records don’t match. The backers are incurring settlement risks as they shift between crypto and state-backed currencies. The lack of central operating authority is dysfunctional. Bitcoin users argued so much over the size of the ‘batch’ at which Bitcoin transactions are recorded that in 2017 the cryptocurrency split into Bitcoin and ‘Bitcoin cash’. Another danger is that some mining group could become dominant enough to take control of a cryptocurrency.

Cryptocurrencies have worrying macro consequences too. Monetary policy might become less effective if much currency were outside the purview of central banks. Central banks would have less seigniorage profits (made from issuing banknotes) to help their government’s budget. Distributed ledgers reduce a central bank’s ability to maintain a centralised register of settlements. Cryptocurrencies might enable capital flight in situations when financial controls have been installed to ensure stability or to limit crime. Cryptocurrencies hamper the ability of central banks to act as the lender of last resort. This could be ruinous during financial crises.

The dangers posed by cryptocurrencies and related platforms and stock exchanges have stirred regulators. They have clamped down on cryptocurrency exchanges and on ‘initial coin offerings’, when people pay to receive cryptographic tokens from a startup that entitles them to some benefit. (The tokens are usually not equity.)

While the systemic risks associated with stateless cryptocurrencies are real, they are low while cryptocurrencies are not widely used. Stateless cryptocurrencies are unlikely to become mainstream anytime soon, especially if authorities get stricter and the cryptocurrency bubble bursts. Chinese beggars and most everyone else will be happy using state-backed currencies, crypto or otherwise, to enjoy the benefits of a cashless world.

By Michael Collins, Investment Specialist

For further insights from Magellan, please visit our website

Important Information: For a list of references used above, please visit the complete article on our website. This material has been prepared for general information purposes and must not be construed as investment advice. This material does not constitute an offer or inducement to engage in an investment activity nor does it form part of any offer or invitation to purchase, sell or subscribe for in interests in any type of investment product or service. This material does not take into account your investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs. You should read and consider any relevant offer documentation applicable to any investment product or service and consider obtaining professional investment advice tailored to your specific circumstances before making any investment decision. This material and the information contained within it may not be reproduced or disclosed, in whole or in part, without the prior written consent of Magellan Asset Management Limited. Any trademarks, logos, and service marks contained herein may be the registered and unregistered trademarks of their respective owners. Nothing contained herein should be construed as granting by implication, or otherwise, any licence or right to use any trademark displayed without the written permission of the owner. No part of this material may be reproduced or disclosed, in whole or in part, without the prior written consent of Magellan Asset Management Limited.

5 topics