The RBA worries it has misread the economy

In the wake of one of the RBA’s largest forecast misses on inflation in decades, Deputy Governor Hauser said this week that:

“the economy may find itself boxed in by its own capacity constraints, like a racehorse trapped against the course fence, unable to surge forward … [such that] there may be little scope for demand growth to rise further without adding to inflationary pressures, and hence there may be little room for further policy easing”.

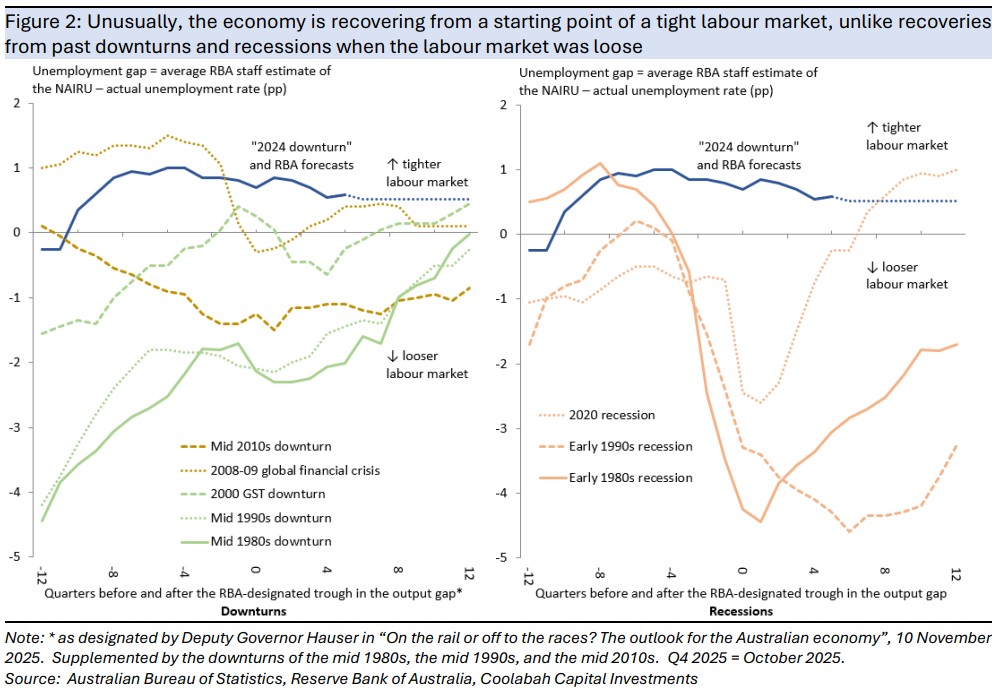

Hauser backed his assessment by showing that the economy was recovering from a starting point of no spare capacity, where RBA staff currently estimate that demand is running slightly ahead of supply, forecasting excess demand to persist over the next couple of years.

This contrasts with past business cycles, when the RBA could lower interest rates without threatening the achievement of low inflation by overheating the economy because demand was less than supply.

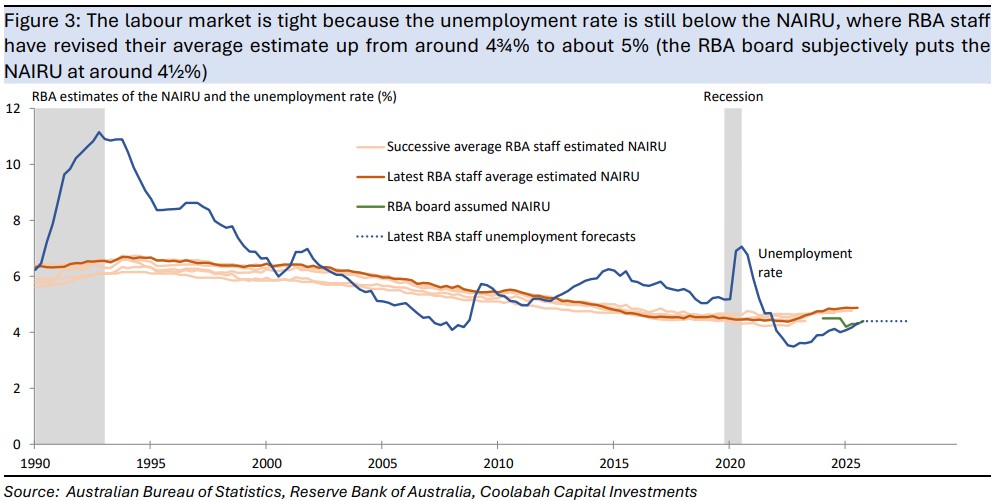

In measuring spare capacity, Hauser focused on the output gap, which compares the level of activity in the economy with the level of potential output. An alternative measure of spare capacity – one that is more relevant because it is used by RBA staff in modelling inflation – compares the unemployment rate with the estimated NAIRU. On this metric, the labour market is tight if the unemployment rate is below the NAIRU and it is loose if the unemployment rate is above the NAIRU.

Like potential output, the NAIRU is unobservable and needs to be estimated, with the average of RBA staff estimates recently increasing from around 4¾% to almost 5%. Given the latest unemployment rate of 4.3% and RBA forecasts that it will hold steady at 4.4% for the next couple of years, this points to prolonged tightness in the labour market.

This is a very different situation from past business cycles, when economic recovery started from a point of spare capacity in the labour market, in that the unemployment rate was below the estimated NAIRU in both recessions and downturns.

The closest parallel would be the very rapid economic recovery from the global financial crisis, when a loose labour market quickly turned into a tight one. The rapid economic recovery from the COVID-led recession of 2020 is a more distant parallel, when an unprecedented fiscal and monetary stimulus took more time to turn a much looser labour market into one as broadly tight as the current labour market.

For his part, Hauser pointed out that the RBA board has continued to override the staff estimate of the NAIRU, effectively pencilling in a lower rate of about 4½% as “[the board has] been attempting in the last period to test how much capacity in the economy there is”.

If the board’s judgment proves correct, then the labour market is almost in balance with the unemployment rate a little below the assumed NAIRU and the staff forecasts implying that it will be broadly in balance as the economy continues to recover over the next couple of years.

A labour market that is almost in balance would still be a rare starting point for an economic recovery and almost as unique as the tight labour market implied by the higher staff estimates of the NAIRU. Compared with the business cycles of recent decades, it would only differ from the global financial crisis, which, as mentioned above, saw the labour market quickly swing from loose to tight.

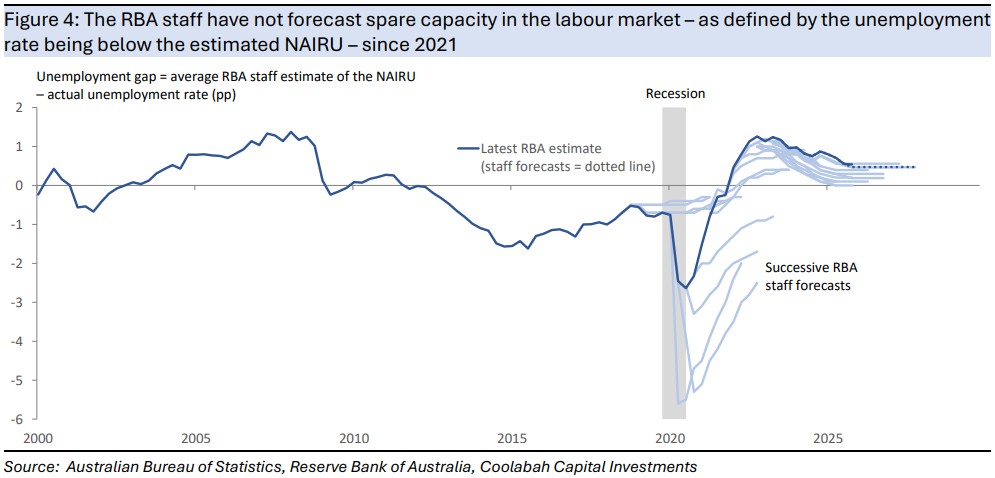

Deputy Governor Hauser framed the economy recovering without the spare capacity common to past recoveries as new news, but it has actually been a feature of every RBA staff economic outlook for some years now. That is, successive Statements on Monetary Policy from 2022 onwards have forecast that the unemployment rate would be either below or, very rarely, in line with the estimated staff NAIRU.

Although the RBA board is now considering whether it is too optimistic in its judgments for both the NAIRU and the neutral policy rate, it probably won’t make up its mind until it sees another couple of quarterly inflation reports and more data on unemployment. The ABS will start publishing a full monthly CPI later this month, but the board will probably wait for the quarterly CPI because some seasonally adjusted monthly prices could be volatile because of their very short history.

At this point, the RBA thinks it won’t have to change its mind on either the NAIRU or the neutral policy rate. The RBA staff forecasts that much higher consumer prices in Q3 were essentially a one-off, with a small spillover to Q4 and a return to low inflation from the start of next year onwards. Such an outcome would see the RBA board stick with the assumption of a 4½% NAIRU, but persistent inflation, particularly in the cost of housing and services prices, would prove confronting and could see the board acknowledge that staff calculations of a higher NAIRU were right and that monetary policy is not as restrictive as it thought.

5 topics