How a trade war could benefit China

The prospect of a trade war has become more significant again. While China may fare worse than the US in this scenario, there are some broader implications that could enhance China's power on the global stage, not least via the One Belt One Road initiative. Here I discuss this and touch on some of the investment implications for Australia.

Export-driven China would fare worse than the US, yes...

Although President Trump’s recent foray into tariffs on steel and aluminium has driven the prospect of a trade war, it builds on a background of increased protectionist sentiments throughout Europe. Claims of dumping, aimed against China, have also been plentiful.

It is generally believed that China would be worse off in the event of a trade war. It has, after all, built its economy on a platform that included a strong export-driven component, supported by the accumulation of large foreign reserves.

The recent call for tariffs from the US was made with reference to national security concerns. A tariff driven by national security concerns, however clumsy this may be to argue to the WTO, is calling out China. Perhaps the game of chicken has moved towards a flashpoint after the circling and strutting which has taken place publicly in Davos, Paris and the South China Sea.

Apparently, trade wars are good and easy to win for the United States, according to Trump. He is probably correct - with a near-term lens. If a trade war were to erupt, in the near term, the US generally comes out quite well in a relative sense although it would not be a favourable development for the world at large.

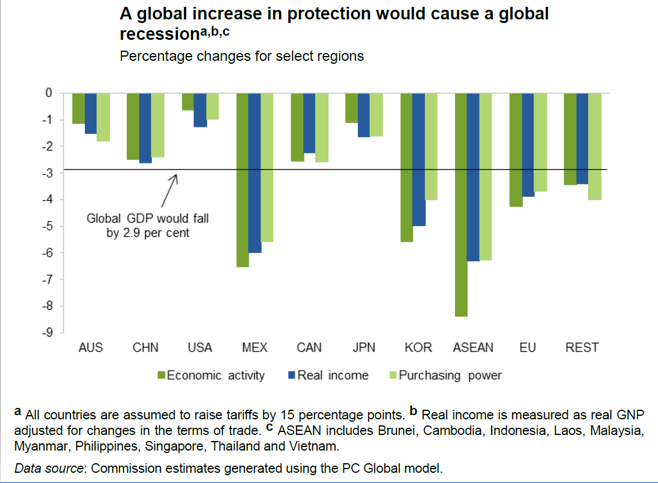

The following scenario relates to a limited trade war where all tariffs are increased by 15%. A full-blown trade war would clearly produce more severe outcomes. A limited war scenario would create a modest recession for the US. China would lose relatively more ground:

Source: Productivity Commission

Would China blink in a trade war stare-down?

But not so fast, Mr Trump.

When President Clinton was in office, he mentioned that one of the greatest questions of the day was how China would choose to define its greatness. Less than 20 years later, that question has been emphatically answered by China’s President Xi. China is to regain its former status as a dominant, if not pre-eminent, power in the world. In the near term, it claims Asia as its sphere of influence.

China’s political apparatus thinks in terms of decades or even generations when seeking these objectives. Political and military power has been consolidated into one man. He is no longer subject to re-elections. The Chinese culture also places relatively more emphasis on knowing one’s place in society and acting collectively. Individual sacrifice is accepted. This clearly contrasts to the individualistic leanings we generally celebrate and thrive in.

With all else equal, China’s governance model can respond and adapt more readily to acute threats, place heavier burdens on its people and think for a longer horizon. It has proven itself to be fearsomely competent in grand strategy. Contrast this to a political system in the United States which is persistently deadlocked on important matters or the five months it has taken Germany just to renew its grand coalition after recent elections. Chicken versus chicken, on an otherwise level playing field, I would be all-in on China’s bird.

However, all else is not equal.

China may not have the economic or military heft of the US at this time, however, it has form in taking on rivals from weak positions. It joined the North when the US entered the Korean Peninsula in 1950, less than a year after enduring a civil war that cost 3.5 million lives. It provoked a much stronger, at the time, Soviet force to quell a border dispute in 1969. China does not have much of a record of blinking during provocations in the recent past. At present, it is holding its gaze whilst the US conducts freedom of navigation exercises in the South China Sea and whilst protecting its commercial assets in Venezuela.

What does it mean to win or to be pre-eminent?

A study at Harvard found that their students, if given a choice, would happily earn less money if it improved their position relative to their peers. This study was not even taken from their esteemed business school. Pre-eminence is simply being first, ahead of the field, whatever the field is doing.

If China favours pre-eminence amongst its peers, over the longer term, the conclusions which might be drawn about trade wars favouring the US might be completely reversed.

In a trade war, the first round goes to the US

Let’s start with the immediate effects. China is growing at approximately 6% per annum over the medium term. The US, perhaps, 3% per annum if we take the optimistic White House projections used to support the recent tax cuts. The impact of the trade war would set the change between the relative economic size of the two nations back a single year or even less. That year might be important for Trump, depending on the timing, but it is nothing in the scheme of 20 years for the revisionist political strategist in Beijing.

What happens to China’s neighbours?

The impact of a trade war on China’s ASEAN neighbours would be very significant: these highly trade-exposed nations generally suffer disproportionately in that scenario.

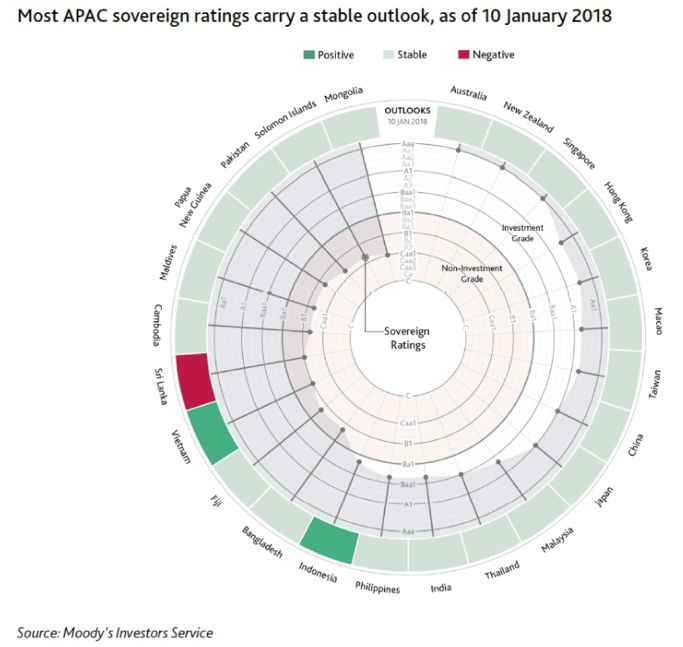

These neighbours already have much weaker financial circumstances and would be cast into a situation that would be reminiscent to the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997. There would be significant capital shortfalls and currencies would be under substantial stress.

Many of China’s near-neighbours also suffer from elevated political risk. Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, Nepal, Bhutan and much of Central Asia are rated by Marsh as having tenuous levels of political stability.

In a crisis, then, there would be much distress around the China’s neighbourhood for economic reasons which could easily cascade to political instability as well. Yet every dangerous situation provides opportunity and the two concepts are indistinguishable in the Chinese language.

If Venezuela, Greece and Pakistan are any guide, Chinese capital will be welcome at such times. Whilst Australia and other parts of the world have become more discerning and protective against China’s economic and political influence, political survival finds a way to overcome objections.

After all, if a US President can seek to create a relatively small number of jobs in the steel industry at a cost to the wider constituency, where are we to draw the lines for political expediency?

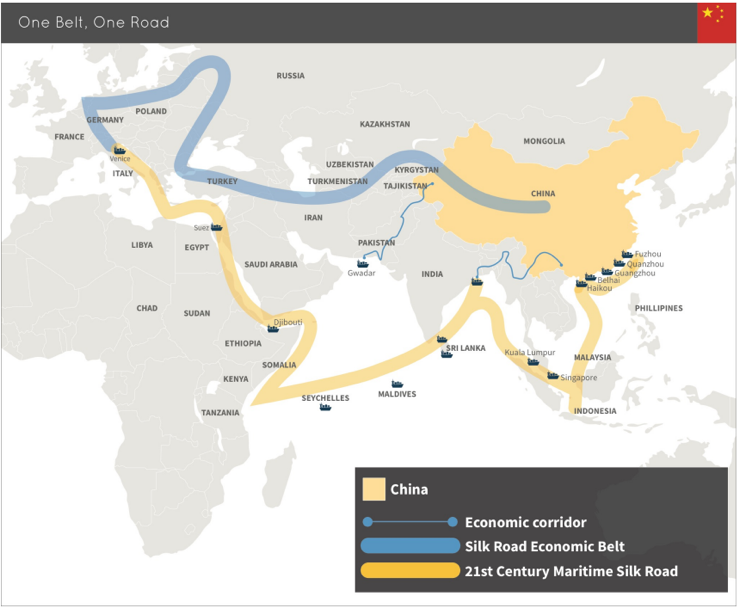

One-Belt One-Road, setting the rules

China has announced its plans to smooth trade and cultural integration. This is a road-map which favours trade as a means to improve circumstances. Given China’s ability to create credit and acquire control of desired physical and political assets, this is a road-map which favours China’s progress to pre-eminence.

Source: Lowy Institute

As China’s investments in the Port of Piraeus (Greece) and Gwadar (Pakistan) demonstrate, it will take advantage of economic stress to develop OBOR on its terms. Its determination to achieve these aims is also clearly evident in protecting its increasingly important shipping routes within the ‘Nine-Dash Line’ in the South China Sea.

OBOR is a historically defining concept. It will transform relationships for those who participate in it. If at least some of these relationships are tilted in China’s favour when the ‘rules’ are set, it will bear fruit over time.

A trade war would provide an abundance of opportunity for China at an excellent juncture of its strategic re-emergence. The weakest neighbours include those along the OBOR map. A trade war opens doors to shift the manner and terms under which the gains from trade along OBOR will be divided. China has already demonstrated its ability for strong influence at the geographical extremes of OBOR.

When viewed with a long lens, with pre-eminence along with absolute GDP as long term goals, a trade war is an opportunity to be taken. There is no reasonable doubt that China would fare better than its neighbours. It is likely to emerge in a better state than Europe on a stand-alone basis.

Healing the rifts

At some point, trade wars will settle. Much as players in the Prisoner’s Dilemma scenario under game theory, we eventually figure out again that cooperation produces better long term outcomes for all. China will obviously have a role in determining the terms and will be a dominant force in determining the length and severity of this event, particularly in intra-regional trade. It will do so with stronger strategic assets in place. A port here, a politician there, a $20bn loan, a long term lease. It all adds up. China will extend its pre-eminence in Asia.

Depending on how the EU reacts to a trade war, China may emerge with even more assets in place despite increasing hesitancy to receive Chinese capital. It is already reaching out to Spain, Portugal and other small European countries. This would build upon Greece’s commitment to serve as China’s gateway to Europe.

With President Trump’s national security perspective and his conflating the German bilateral deficit with military expenditure, it is unclear that the US and Europe would be deft enough to contain China’s efforts to improve its position against them.

Whilst China might take a near term pay-cut and fall further behind some of its peers for a while, the longer term sees a trade war favouring China’s position in Asia with high likelihood. Europe will be weakened. With an “America First” bias and increasingly isolationist stance from its NATO ally, Europe may either have to tough it out, suffering a damaging rise in populism and instability, or accept a lesser evil of Chinese help.

A world fractured by a trade war may well emerge more integrated, especially along the OBOR. The terms for participation would favour China even more. What a coup.

Investment Implications

Not knowing how the chaos of a trade war would truly play out makes distinct investment suggestions difficult to produce. The emergence of a trade war in the near term is a risk scenario, not a base case.

Whilst economists urge sense to prevail on the basis on protecting economic growth, China has its eyes on pre-eminence as well. Its interests may favour a period of chaos or, at least, not fear it quite as much as President Trump might hope. To that extent, risk skews from this source may be more to the downside than more generally believed.

Australia is reasonably well placed. Our exports of tourism, education and raw materials that are crucial to China and Japan makes us somewhat resilient.

Further, as China’s economy slows in a trade war, it will stimulate, and construction will be a part of this.

The Australian dollar remains a reliable safety cushion and will likely trade as other emerging markets currencies in the period – badly. We may even get off quite lightly.

9 topics